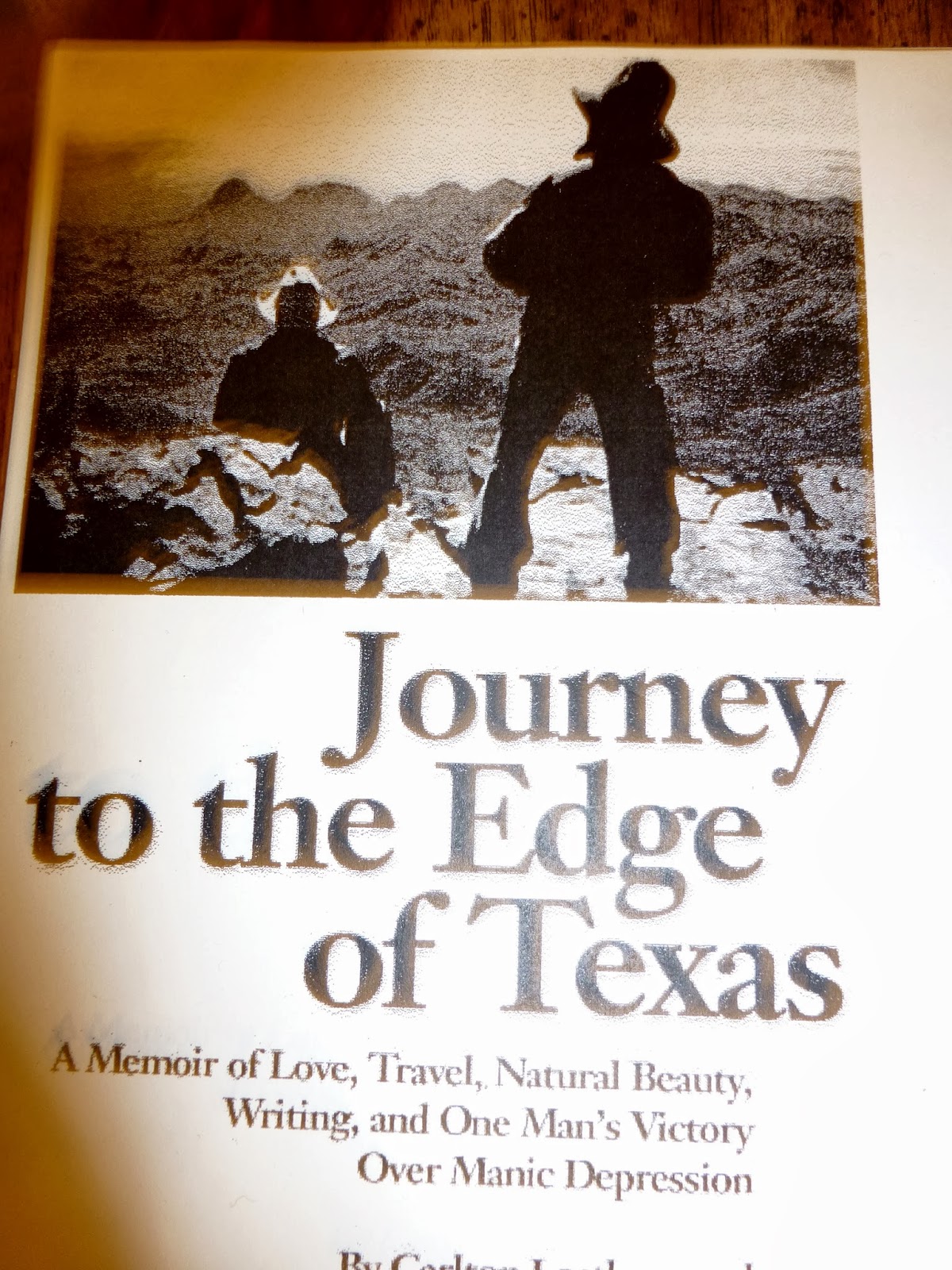

Journey to the Edge of Texas

(Editor's Note: This is the introduction to a book written by me circa 2000. This is the first printing. A chapter will appear each week.)

Mental illness derailed my train of thought a dozen times as I contemplated and worked on this book. I began writing it twenty years ago as a journal, but it was relegated to a side track as my psychotic explosions intensified. I often lost reality for three months at a time. Then a miracle drug, Risperdal, came my way and I improved--significantly. The journal got back on track.

This narrative tells of my odyssey through the wonders and beauties of Texas, a journey of heart, but the book also follows a parallel rail, a journey into the center of the brain. Try as I might, I cannot ignore my brain. At first I mostly wanted to offer something steeped in nature, outdoor recreation, and history. The collected wisdom of the caretakers of our landmarks have found its place in this work, too. But the dark moods that interrupted my efforts to create a fireside "chat "--they thunder to be heard as well. Having repelled them leads me to also tell the story of a scientific achievement that offers a beacon of hope to fellow sufferers.

I enrolled in a Continuing Studies course on memoirs at Rice University with the objective of breathing new life into this writing project. One of the first things the instructor asked us to do was to describe our intended reader. In retrospect, I must face the fact that I have done what I didn't want to do. I have written with the most appeal for those with mental illness. At the outset, and fooling myself all along, I considered the subject too depressing and figured that enough volumes have recorded all-too-many psychotic episodes.

I do brush over my episodes. I believe the interested will benefit primarily from the views of doctors at a federal health discrimination trial. A national authority on manic depression focused on the illness in expert testimony. A benevolent doctor of the plaintiff was apparently too close to the case. And the expert witness for the defense, with hindsight, was the one who best summed up the implications of my fifteen extreme bouts with psychosis.

The ill can also take comfort in knowing of an East Texas state hospital that is more like a wooded college campus than a stereotypical "nut" house. Its treatment, take heart, is on the cutting edge.

Given that I suffered in part from a trauma created in the workplace, I had the opportunity to claim disability. I was also blessed with a doctor who stepped in to keep me off the streets where many with my acute condition languish.

I think many who go in and out of mental hospitals as I have will celebrate that I and they can now find freedom in the discovery of new medication. It allows many to live outside hospitals for long stretches. The advancement is not a panacea, however. The best of the drugs can cause neurological side effects such as tremors and Parkinson's disease.

But this book is not altogether for, or about, the afflicted. Many readers, I hope, will go with me beyond the darkness to share in an exaltation of our landscape, thrill to the awareness in our nature of flora and fauna that overcomes an evil wind, and who may even enjoy observing my-all-too-human weaknesses as I literally lose a woman friend on a mountain trail.

I have also sandwiched in other aspects of my being, such as touching on marriage (why I didn't) and death (its coming to the fore in more frequent funerals). I have not taken much note of things before age forty (about the time of the confluence of manic depression and the odyssey). My writing instructor, however, gave the class an assignment to relate our earliest childhood memory. And I oblige.

I must forewarn you that my college English professor gave me the same assignment. When I was through and he passed back the paper, he said I couldn't have remembered what I wrote. In truth, I might have been remembering from pictures, and I don't know for sure.

I was four, and we were living in an orange frame apartment over a store that sold lumber and hardware. This was in McCamey, Texas, out in the Permian Basin President George W. Bush is so proud to include in his childhood history. My one sure recollection is a sandstorm that billowed into our residence. I remember the thickness of the air. I don't know how he--or we--survived.

Stairs led from the front door, trimmed in white, to the ground, and off to the side was a tin roof, over the lumber yard. We had a pet, a white and black fox terrier, which my paternal grandfather had given me, and we named her Lady.

She had one trick. She may have had others, but that I don't remember.

When there were passersby, she would jump from the stairs onto the tin roof and then run to the edge--it had a pitch--hang her head over, and bark. She was genuinely on the edge.

My thoughts of those days, though, are fleeting. I have found inspiration to finish the writing task before me in the award-winning autobiography of Christopher Nolan. A quaedriplegic, he wrote Under the Eye of the Clock by having someone hold his head while he tapped at a typewriter with a stick attached to his forehead.

My family has helped me. My parents' final Christmas gift, when I was down and they were going down, was a computer that would allow me to work at home. My mother never accepted my disability as permanent. "What a waste," she said, pausing before adding "of money."

What of the old word processor I had started the journal on? A friend suggested I "bronze it like baby shoes."

No comments:

Post a Comment