Photos by Voni Glaves

|

| Primary Voting is happening now. Vote Early and Often. |

|

| Debbie knows the way to a goat's heart is FRITOS and Milk! |

|

| Paul interview the candidates. |

|

| While Mom keeps a lookout, the candidates plot strategy |

|

| Milk Break |

|

| Annabell is leading by a tiny margin. |

|

| Time to go back to work . . . |

Journey to the Edge of Texas

Chapter 2--Poetic Derivative

A

relative's life resembles mine in the written word and in mental

faults. Either it wasn't known or the family didn't talk about it at

the time I first entered the hospital. From what I learned at a panel

discussion of doctors, it would have helped in the diagnosis of my

illness.

As it

was explained to me, the initial psychosis of a manic depressive or a

schizophrenic looks similar. A psychiatrist will have something to go

on in differentiating the two in the patient if informed of such

illness among his relatives.

I would

learn years later that I was first called a schizophrenic, which

could account for my not getting treatment for manic depression for a

decade. Yes, it might have helped, though the drugs that did weren't

around.

But

even today my genetic interest focuses on Kenneth. Uncle Kenneth. On

the paternal side. Leatherwood.

I

participated in his eulogy and did not recognize his closeness. I

quoted him:

"The

sadness of farewell is good,

"It

speaks of love divine."

He

wrote poetry as a pastime, as did his father (my grandfather). I

never bothered to take up the habit, but when the first piece of this

memoir was compared to poetry, I became more attentive. Here was

linkage that swallowed the duels with demons that we had both

inherited, the two-edged sword of our genetic makeup.

As

river guide Bones would say when talking about the little isolated

mountain ranges below the Rocky Mountains, "They are like little

chips off the great block." And so were we.

Maybe

all along I did reserve a special place for my uncle. In the shared

illness of manic depression. I once in a delusion thought of him as

Walt Disney. I was playing a record from a 1958 visit to the

Disneyland theme park and imagined Kenneth, not Disney, was

moderating the tour from the puff of a steam locomotive out of the

station to the adventures of a river jungle. This was a strange

twist, because a favorite uncle on the maternal side had flown me to

the then-new fantasyland.

Uncle

Kenneth's medical history pains me. He did not have the benefit of

most psychiatric drugs, not even lithium, for most of his nights, and

the terror (I will call it that, for that is what delusions usually

are, contrary to some learned thought that we patients are enjoying

them)--the terror increased with age. I first became aware of his

problem when my dad was called late Christmas Eve to retrieve his

brother from a country jailhouse near the Trinity River. It wasn't

that he was violent, more that he was "out of his head" and

a danger driving. No rural hospital was nearby to treat him, so the

small jail became a safe haven--as it would for me in one of my later

episodes in Oklahoma.

When my

family got Uncle Kenneth the next day, I took the wheel of his car,

and he climbed in beside me. He splashed on a cheap cologne to mask

the smell of days on the road without a bath. I made reference to the

fact that he should be in a hospital. "Butch, that doesn't

become you," he said, irritated. He had, until then called me

Butch with fondness.

Uncle

Kenneth would not have benefited from the rudimentary drugs available

then, even if he would have taken them, which he would not. He damned

all drugs and doctors, would not take medicine, and certainly would

not have stood for the laboratory tests that go with lithium.

Why

was he crisscrossing the state? He was looking for an old girl

friend, he said. I could relate later, having stomped through Phoenix

and swamping The New York Times on

similar quests. In Kenneth's instance (which took place in the early

eighties) the lost love dated back to the Depression. He didn't

mention his wife of forty years, left alone and apprehensive that

particular Christmas.

In

finer moments Uncle Kenneth penned poems that, as I said at his

graveside service, revealed his values, his religion, and his

reverence toward others. Several were read.

"Enduring,"

he called this one:

...And

I met so many people

Who

like me were searching too,

And

we climbed upon a steeple

Just

to watch for folks like you.

Thus

my patience was rewarded,

And

the end reward I gained;

I

no longer was retarded--

My

happiness no longer feigned.

I

had found a thing enduring;

It

would never have an end;

It

would have the power of curing:

I

had found myself a friend.

He

received inspiration from nature.

A

trip to Aspen leaves you gasping.

And

the ski life finds you grasping,

Not

alone the chair you ride in,

But

the God we all abide in;

Grasping

that His work tremendous,

Huge,

colossal and stupendous,

Dwarf

the human mind's conception

of

God's glorious reception

...We

are micro-organisms;

It

is He who made the chasms,

It

is He who made it all;

From

His grace let us not fall.

Dr.

Robert Hirschfeld, the chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at

the University of Texas at Galveston, was asked, "Does this

illness strike creative people such as writers, entertainers, and

musicians?"

His

answer, at my federal health discrimination trial against The

Houston Post was, "There's an

increased frequency of bipolar illness (the modern term for manic

depression) in such people."

"Why

is that?" Steve Petrou, my attorney, asked. "Why does it

target some of those creative people?"

"People

who are creative go beyond the bounds of the more normal conformity

in terms of thinking and in terms of behavior, and there are some

psychiatric illnesses where that happens and certainly bipolar

illness is one of those.

"The

problem is when it gets completely out of hand, these peple are not

productive. ...Kay Jamison recently wrote about the lives of a number

of people (who) had bipolar illness. ...Many of these artists or

composers would have very productive periods until it got frankly

manic in which case--or would be depressed in which case--they were

not productive at all."

(Kay

R. Jamison's book is Touched With Fire:

Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic.)

Uncle

Kenneth suffered severe brain damage when he drove in front of an

eighteen-wheel truck while manic. He regained only limited

recognition during long years in a nursing home and died in 1998. He

had written effusively in a narrative poem of family history and of a

rosebush planted by his pioneer grandmother in 1882:

Now

in comfort I look westward

As

my evening shadows lengthen,

And

I venture forth one pleading;

I

will walk my way in comfort,

Soothed,

serene, and witbout anguish,

If

you promise me but only

I'll

be buried in Lampasas,

In

the Oak Hill Cemetery,

Where

grows the Rose of Life Eternal,

There

lives the Rosebush Everlasting.

It was

a promise kept.

Carlton Leatherwood's America:Texas Prepared Me for This Journey

to See Our Country

In

the 1980s I got close and personal to Texas. Now begins a similar

pilgrimage to see America. Our state took an untold number of forays

to grasp even a modicum of understanding of my rich heritage. Today,

look back with me to those golden years, especially the time spent in

the Big Bend.

Here

is what I said in an unpublished book:

If

I were as wise as prize-winning author John Steinbeck, I would have

known that this journey--the compilation of a book called "The

Other Side of Texas"--would end earlier than anticipated. He

said before visiting Texas and the Deep South that his search for

America "had been like a full dinner of many courses, set before

a starving man. At first he tries to eat all of everything, but as

the meal progresses he finds he must forgo some things to keep his

appetite and his taste buds functioning."

My

journey started innocently enough. Friends up in New England wanted

to travel in Texas as I had done in their part of the country. I

wasn't sure what to show them, however, so I looked around. Taking

them to see an oatmeal sculpture of an armadillo holding a bottle of

Lone Star beer didn't seem right. Too much of an overstatement of

state chic. I went on to search for subtler pleasures.

I

found excitement in an armadillo on the loose in the lush woodland of

East Texas. I discovered that the only wild flock of one of the

rarest birds on earth, the whooping crane, is the superlative reason

for visiting the Coastal Bend of Texas. (More than 400 of the roughly

540 other species of birds in the state also live or migrate there.)

For some visitors to the state, in fact, birding may surpass all

other attractions; national authority Roger Tory Peterson says Texas

boasts the greatest variety in the country, with California a distant

second.

The

tremendous beauty of the coastal region is not immediately apparent.

Just as mountains were considered impediments to travel before

artists and writers awakened us to their aesthetic quality, so the

flat marshes and shallow bays pass monotonously before the untrained

eye. It helps to read about the birds, grasses, and other life in

those estuaries where such dining delicacies as shrimp mature

rapidlly and blue crabs thrive. You then possess something with which

to contemplate the richness of the land. And it is rich. Roy

Bedichek, a nature writer, said the Texas coast is a storehouse of

natural wealth unparallelled elsewhere in the world in so little

space. He noted the commingling of such natural elements as oil and

gas, farmlands, harbors, climate, and the fishing industry.

The

more I travelled the more I got to know the people of Texas. One of

my favorites was a consummate storyteller by the name of Hallie

Stillwell, who had a ranch in the Big Bend region of West Texas. On a

wintry day in 1985 she spoke in possibly the only sunny spot in the

state. A massive snowstorm had blanketed the desert and many other

areas with ice crystals. The occasion, however, was appropriate

enough--the Cookie Chilloff at Terlingua, a spoof of the more

publicized Chili Cookoff.

"I

like to talk about our old citizens, our old cowboys," Stillwell

said. "One I like to tell about is Aaron Green. We always

called him Noisy. He lived on the east side of the Chisos Mountains

at a place called Dugout. One time he was asked what he did at a

dance. He said he took the school teacher. That's all he said.

"The

next day somebody asked the school teacher if Noisy said anything. It

was a twenty-mile ride horseback down there and twenty-mile ride

back. They danced all night. The teacher said, 'Oh, yeah, Noisy

talked quite a bit." She said as they rode down he said, 'You

see that owl sitting over in the tree?' The next day as they came

back, he said, 'Ain't it got big eyes.'"

"Another

tale is on Lou Buttrill and John Henderson," Stillwell

continued. "Lou and the neighbors were having this roundup, and

in those days all of the ranchers gathered together and worked their

cattle from one outfit.

"Lou

happened to have charge of this one. This early morning they were

roping out the mounts for each cowboy, so Lou said to John, 'I want

you to ride Old Don.' John said, 'I don't want to ride Old Don; he's

the worst pitching horse in this country.' Lou said, 'Why old Don

hasn't pitched in a year.'

"So

John said, 'Okay, I'll ride him.' He saddled him up and when he did

Old Don just let him have the awfullest pitching that ever was. John

was one of the best riders in the country, and he rode him all right.

After the horse settled down and they were driving the cattle, John

rode up to Lou and said, 'I thought you told me Old Don hadn't

pitched in a year.' Lou said, 'He ain't been rode in a year.'"

By

the time I got to the Hill Country, aptly called the heartland of

Texas, the simple meal of travel I was preparing for my out-of-state

friends had turned into a feast. To the courses of natural history

and people I had added a third dimension, physical activity.

I

had decided I would immerse them in two extremes of the spectrum of

water excursions. We would raft the beautiful desert canyons of the

Rio Grande and frolic in old-fashioned swimming holes in the hills

that an 1854 traveler, the famous landscape designer Frederick Law

Olmsted, described thus: "For sunny beauty of scenery and

luxuriance of soil, it stands quite unsurpassed in my experience, and

I believe no region of equal extent in the world can show equal

attractions."

I

could have sandwiched in any number of other activities, including

ranch life or more resort-oriented diversions such as tennis. Or a

blend of both: If the laid-back life of a ranch had appeal, but a

person's game was tennis, not horses and cattle, John Newcombe's

Tennis Ranch awaited us. The instruction in a five-day package at

Newk's is not laid-back, but life after the courts moves at a slower

pace in and around a fine old rock ranch home on a hill blanketed

with acorns in the fall. And any time you sit down to a meal, you sit

down with people who have one thing in common: they love tennis.

I

was relaxing in the whirlpool after a particularly tough day and

asked a group of Oklahoma women who come every year why they put out

so much energy. It couldn't be for all the Gatorade and oranges a

person wants at breaks on the courts. No, one told me, "It's

three hours less than I iron a week."

Newcombe,

an Australian who was singles champion at Wibledon in 1967, 1970,

and 1971 and the U.S. Open in 1973, bought the ranch with Graeme

Mozeley and Clarence Mabry, who coached a string of world-class

players at Trinity University in San Antonio for twenty years. The

Aussie flavor is found at the bar in Foster's beer. The brew comes in

a container the size of an oil can.

I

started bumping into things cosmopolitan at Newk's. That shouldn't

have surprised me, since Texas, like the whole United States, is a

melting pot. Some 30 cultural and ethnic groups settled it. And at

the tennis ranch in late afternoon teenagers with skins of varied

hues filled up many of the courts.

I

bumped into all sorts of cutural artifacts more often associated with

cities before I finished visiting the isolated parts of Texas. I ran

into the name of Monet in the desert of the Big Bend. At the ghost

town of Terlingua I heard song about Isla Mujeres, an island

destinatin of Houston yachtsmen across the Gulf of Mexico. And at the

tiny classical music oasis of Round Top east of the Hill Country I

learned to appreciate Schubert.

By

this time I was yearning to add to the book the intellectual pursuits

of the cities, where the dreamers lead campaigns for great

symphonies, theaters, and libraries and plan America's charges into

space. But I had gorged too much for one journey. The taste buds

weren't responding. And probably a publisher wouldn't to such a

gluttonous volume. My friends would have to settle for the grand

architecture of Houston on the way from the airport.

My

journey also took a nostalgic curve through East Texas, as good trips

sometimes do. When I was growing up, my father sold drilling muds and

chemicals, moving his family throughout the Texas oil fields before

settling in Beaumont, the site of the first major oil gusher. The oil

well, the Lucas discovery well in the Spindletop field, had roared in

January 10, 1901. Along the way, driller Curt Hamill needed to flush

out the cuttings. He drove cattle into a nearby pond, and their

milling-about produced the mud that, when pumped into the well, would

bring up the cuttings. My dad didn't know his job, by then much more

sophisticated, had developed almost in the backyard of our family

home.

On

my trip, I drove north through the pine forests, searched out the

first steel oil tanks and toured the East Texas Oil Museum at

Kilgore, not far from where I had started school. My mother, with me

along as a child, had stopped at roadside stands for produce. Now I

sought out fresh tomatoes, beans, and squash at farmers' markets in

Lufkin and Tyler. Later a friend and I picked blueberries in an open

field. An employee at a small restaurant in Jefferson was kind enough

to wash and serve them with ice cream. And it is to Jefferson that I

bring fellow travelers who long to taste the nostalgia for a simpler

life during the Victorian period.

Texas

is all things to all people. The mix of cultures has created a breed

of people not unlike the longhorns, the tough cattle of crossed

ancestry that also developed on this land. We Texans share the

resourcefulness of the Dutch, the industry of Germans, the colorful

dress of the Spanish, and the indomitable spirit of the British. To

survive, many have to have the same toughness of the cattle. Survive,

and thrive, they do.

The

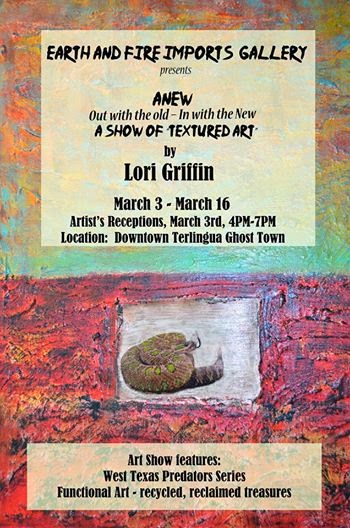

Coffee Cup: Artist Lori Griffin

To

Open a Show With Lots of Texture

"ANEW,"

the art show of Lori Griffin, opens Monday at Earth and Fire Imports

Gallery in Terlingua and runs through March 16.

It

is a show of series, one inspired by a book about West Texas

creatures that the the artist is writiing for her two-year-old

grandson.

There

will be four pieces of the West Texas Predator Series in the show.

Other series include Tree Folk and Colorful Crosses.

"But

as always, there are functional pieces," Lori said. "And I

believe that everyone should be able to afford art, so the prices

range from $10 to $800. The art is unique and intended for both kids

and adults to enjoy."

She

said there is lots of texture.

"Every

piece is made using upcycling," she explained. "I take

"old" materials to make "new" art. Making

upcycling art requires combining methods and techniques. It is

challenging and time consuming, and draws on ones imagination.

"The

end result is funky collage art," she concluded. "I love

making it!"

The

Earth and Fire gallery is in Ghost Town.

The

artist's reception for the Out with the Old--In with the New show of

textured art is Monday from 4 to 7 p.m.

Oh,

and that lucky grandson is named Logan.

.jpg) |

| Rush Warren and Frac on top of Tres Cuevas |

From

the top of Tres Cuevas Mountain, you can see forever, but at the

lower elevation, where frac'ing is discussed, the view is not so

clear.

I

accepted the invitation of Rush Warren to visit him at Lone Star

Ranch, near the base of the mountain. It is his and wife Penni's

home. The ranch is north of Lajitas International Airport and is

named after Lone Star Mine, which is located on the top and back side

of Tres Cuevas Mountain.

Rush

says the original mining town of Terlingua was here. It is his

understanding that 3,000 to 5,000 people inhabited the town around

1900. Several ruins still stand, including the Terlingua Jail and a

machine shop.

Rush

is president of Warren Acquisition, Inc., whose business is oil and

gas exploration. He had told me that frac'ing in oil and gas fields

dated to the 1970's. With documentary movies like "Gasland,"

which portrayed gas coming out of water faucets being ignited and a

story last week headlining "Big Oil, Bad Air: Fracking the Eagle

Ford Shale of South Texas," I wanted to get an oilman's opinion.

We

had exchanged email on the subject, and Rush sent me an article by

the Geological Society of America (GSA) that it said was a primer for

the general public and journalists. Rush gave the article a solid "A"

and nearly an "A plus." To begin the Big Bend Times ongoing

coverage of the issue, I will quote liberally from the write-up.

Rush

does take exception with the article's use of the word fracking

instead

of frac'ing.

Incidentally, he named his labrador retriever Frac more than nine

years ago.

As

we were seated on his sofa, the area oilman and neighbor stood by

this email assertion:

"I

hear of people claiming to be environmentalists banging the war drums

of environmental concerns of frac'ing, which for some reason they

call 'fracking.' I have yet to actually hear of anything that has

actually happened as a direct result of frac'ing.

"I

have heard them attempt to claim that it causes earthquakes and water

quality issues, among other disasters in an attempt to scare gullible

people, but facts backing their stories are lacking. It is

interesting that even though we have been using huge frac jobs since

the 1970's that all of a sudden now it causes earthquakes.

"Frac'ing

may be new news to them, but oil people have known about fracs for

decades. These stories are created to instill fear in the people in

order to promote a political agenda against the use of hydrocarbons

in general."

According

to the GSA report, hydraulic fracturing, also called frac'ing, is a

technological process used in the development of natural gas and oil

resources. Used commercially since the 1940s, it has only relatively

recently been used to extract gas and oil from shales and other tight

reserves. Development of lower cost, more effective fracturing

fluids, with horizontal well drilling and subsurface imaging, created

a technological breakthrough that is largely responsible for the

increase in domestic production of shale gas in the last few years

and longer for tight gas.

Continued

use of hydralic fracturing can be expected, given projections of

future shale gas and tight gas contributions to total U.S. gas

production, unless it is banned or replaced by other technologies.

Hydraulic fracturing has expanded oil and gas development to new

areas of the United States and internationally, including Canada,

Australia, and Argentina. In contrast, some governments have limited

the use of it. For example, South Africa only recently lifted a

moratorium, New York State has a moratorium, and France has banned

its use.

Hydraulic fracturing has become

a highly contentious public policy issue because of concerns about

the environmental and health effects of its use. What are the

environmental risks? What are the health risks from the chemicals

injected into the ground? Will it take away water needed for food

production and cities? Does it trigger earthquakes? Does expansion of

this technology for fossil fuels mean a decreased commitment to

renewable energy technology?

Oil

and natural gas, which are hydrocarbons, reside in the pore spaces

between grains of rock (called reservoir rock) in the subsurface. If

geologic conditions are favorable, hydrocarbons flow freely from

reservoir rocks to oil and gas wells. Production from these rocks is

traditionally referred to as "conventional" hydrocarbon

reserves. However, in some rocks, hydrocarbons are trapped within

microscopic pore space in the rock. This is especially true in

fine-grained rocks, such as shales, that have very small and poorly

connected pore spaces not conducive to the free flow of liquid or gas

(called low-permeability rocks).

Natural gas that occurs in the

pore spaces of shale is called shale gas. Some sandstones and

carbonate rocks (such as limestone) with similarly low permeability

are often referred to as "tight" formations. Geologists

have long known that large quantities of oil and natural gas occur in

formations like these (often referred to as tight oil or gas).

Hydraulic fracturing can enhance the permeability of these rocks to a

point where oil and gas can economically be extracted.

Frac'ing

is a technique used to stimulate production of oil and gas after a

well has been drilled. It consists of injecting a mixture of water,

sand, and chemical additives through a well drilled into an oil- or

gas-bearing rock formation under high but controlled pressure. The

process is designed to create small cracks within (and thus fracture)

the formation and propagate those fractures to a desired distance

from the well bore by controlling the rate, pressure, and timing of

fluid injection. Engineers use pressure and fluid characteristics to

restrict those fractures to the target reservoir rock, typically

limited to a distance of a few hundred feet from the well. Proppant

(sand or sometimes other inert material, such as ceramic beads) is

carried into the newly formed fractures to keep them open after the

pressure is released and allow fluids (generally hydrocarbons) that

were trapped in the rock to flow through the fractures more

efficiently.

Some

of the water/chemical/proppant fracturing fluids remain in the

subsurface. Some of this fluid mixture (called flowback water)

returns to the surface, often along with oil, natural gas, and water

that was already naturally present in the producing formation. The

natural formation water is known as produced water and much of it is

highly sailine. The hydrocarbons are separated from the returned

fluid at the surface, and the flowback and produced water is

collected in tanks or lined pits. Handling and disposal of returned

fluids has historically been part of all oil and gas drilling

operations, and is not exclusive to wells that have been

hydraulically fractured. Similarly, proper well construction is an

essential component of all well-completion operations, not only wells

that involve hydraulic fracturing. Well completion and construction,

along with fluid disposal, are inherent to oil and gas development.

.jpg) |

| Desolate machine shop |

.jpg) |

| Terlingua Jail |

No comments:

Post a Comment