Carlton Leatherwood's America:Texas Prepared Me for This Journey to See Our Country

In the 1980s I got close and personal to Texas. Now begins a similar pilgrimage to see America. Our state took an untold number of forays to grasp even a modicum of understanding of my rich heritage. Today, look back with me to those golden years, especially the time spent in the Big Bend.

Here is what I said in an unpublished book:

If I were as wise as prize-winning author John Steinbeck, I would have known that this journey--the compilation of a book called "The Other Side of Texas"--would end earlier than anticipated. He said before visiting Texas and the Deep South that his search for America "had been like a full dinner of many courses, set before a starving man. At first he tries to eat all of everything, but as the meal progresses he finds he must forgo some things to keep his appetite and his taste buds functioning."

My journey started innocently enough. Friends up in New England wanted to travel in Texas as I had done in their part of the country. I wasn't sure what to show them, however, so I looked around. Taking them to see an oatmeal sculpture of an armadillo holding a bottle of Lone Star beer didn't seem right. Too much of an overstatement of state chic. I went on to search for subtler pleasures.

I found excitement in an armadillo on the loose in the lush woodland of East Texas. I discovered that the only wild flock of one of the rarest birds on earth, the whooping crane, is the superlative reason for visiting the Coastal Bend of Texas. (More than 400 of the roughly 540 other species of birds in the state also live or migrate there.) For some visitors to the state, in fact, birding may surpass all other attractions; national authority Roger Tory Peterson says Texas boasts the greatest variety in the country, with California a distant second.

The tremendous beauty of the coastal region is not immediately apparent. Just as mountains were considered impediments to travel before artists and writers awakened us to their aesthetic quality, so the flat marshes and shallow bays pass monotonously before the untrained eye. It helps to read about the birds, grasses, and other life in those estuaries where such dining delicacies as shrimp mature rapidlly and blue crabs thrive. You then possess something with which to contemplate the richness of the land. And it is rich. Roy Bedichek, a nature writer, said the Texas coast is a storehouse of natural wealth unparallelled elsewhere in the world in so little space. He noted the commingling of such natural elements as oil and gas, farmlands, harbors, climate, and the fishing industry.

The more I travelled the more I got to know the people of Texas. One of my favorites was a consummate storyteller by the name of Hallie Stillwell, who had a ranch in the Big Bend region of West Texas. On a wintry day in 1985 she spoke in possibly the only sunny spot in the state. A massive snowstorm had blanketed the desert and many other areas with ice crystals. The occasion, however, was appropriate enough--the Cookie Chilloff at Terlingua, a spoof of the more publicized Chili Cookoff.

"I like to talk about our old citizens, our old cowboys," Stillwell said. "One I like to tell about is Aaron Green. We always called him Noisy. He lived on the east side of the Chisos Mountains at a place called Dugout. One time he was asked what he did at a dance. He said he took the school teacher. That's all he said.

"The next day somebody asked the school teacher if Noisy said anything. It was a twenty-mile ride horseback down there and twenty-mile ride back. They danced all night. The teacher said, 'Oh, yeah, Noisy talked quite a bit." She said as they rode down he said, 'You see that owl sitting over in the tree?' The next day as they came back, he said, 'Ain't it got big eyes.'"

"Another tale is on Lou Buttrill and John Henderson," Stillwell continued. "Lou and the neighbors were having this roundup, and in those days all of the ranchers gathered together and worked their cattle from one outfit.

"Lou happened to have charge of this one. This early morning they were roping out the mounts for each cowboy, so Lou said to John, 'I want you to ride Old Don.' John said, 'I don't want to ride Old Don; he's the worst pitching horse in this country.' Lou said, 'Why old Don hasn't pitched in a year.'

"So John said, 'Okay, I'll ride him.' He saddled him up and when he did Old Don just let him have the awfullest pitching that ever was. John was one of the best riders in the country, and he rode him all right. After the horse settled down and they were driving the cattle, John rode up to Lou and said, 'I thought you told me Old Don hadn't pitched in a year.' Lou said, 'He ain't been rode in a year.'"

By the time I got to the Hill Country, aptly called the heartland of Texas, the simple meal of travel I was preparing for my out-of-state friends had turned into a feast. To the courses of natural history and people I had added a third dimension, physical activity.

I had decided I would immerse them in two extremes of the spectrum of water excursions. We would raft the beautiful desert canyons of the Rio Grande and frolic in old-fashioned swimming holes in the hills that an 1854 traveler, the famous landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted, described thus: "For sunny beauty of scenery and luxuriance of soil, it stands quite unsurpassed in my experience, and I believe no region of equal extent in the world can show equal attractions."

I could have sandwiched in any number of other activities, including ranch life or more resort-oriented diversions such as tennis. Or a blend of both: If the laid-back life of a ranch had appeal, but a person's game was tennis, not horses and cattle, John Newcombe's Tennis Ranch awaited us. The instruction in a five-day package at Newk's is not laid-back, but life after the courts moves at a slower pace in and around a fine old rock ranch home on a hill blanketed with acorns in the fall. And any time you sit down to a meal, you sit down with people who have one thing in common: they love tennis.

I was relaxing in the whirlpool after a particularly tough day and asked a group of Oklahoma women who come every year why they put out so much energy. It couldn't be for all the Gatorade and oranges a person wants at breaks on the courts. No, one told me, "It's three hours less than I iron a week."

Newcombe, an Australian who was singles champion at Wibledon in 1967, 1970, and 1971 and the U.S. Open in 1973, bought the ranch with Graeme Mozeley and Clarence Mabry, who coached a string of world-class players at Trinity University in San Antonio for twenty years. The Aussie flavor is found at the bar in Foster's beer. The brew comes in a container the size of an oil can.

I started bumping into things cosmopolitan at Newk's. That shouldn't have surprised me, since Texas, like the whole United States, is a melting pot. Some 30 cultural and ethnic groups settled it. And at the tennis ranch in late afternoon teenagers with skins of varied hues filled up many of the courts.

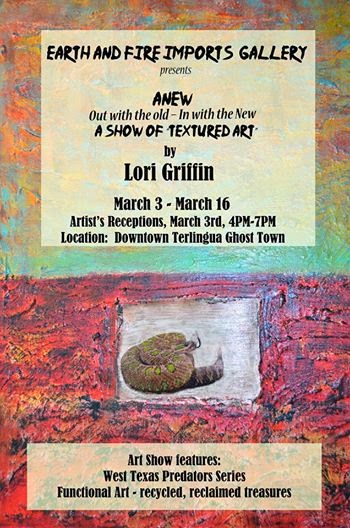

I bumped into all sorts of cutural artifacts more often associated with cities before I finished visiting the isolated parts of Texas. I ran into the name of Monet in the desert of the Big Bend. At the ghost town of Terlingua I heard song about Isla Mujeres, an island destinatin of Houston yachtsmen across the Gulf of Mexico. And at the tiny classical music oasis of Round Top east of the Hill Country I learned to appreciate Schubert.

By this time I was yearning to add to the book the intellectual pursuits of the cities, where the dreamers lead campaigns for great symphonies, theaters, and libraries and plan America's charges into space. But I had gorged too much for one journey. The taste buds weren't responding. And probably a publisher wouldn't to such a gluttonous volume. My friends would have to settle for the grand architecture of Houston on the way from the airport.

My journey also took a nostalgic curve through East Texas, as good trips sometimes do. When I was growing up, my father sold drilling muds and chemicals, moving his family throughout the Texas oil fields before settling in Beaumont, the site of the first major oil gusher. The oil well, the Lucas discovery well in the Spindletop field, had roared in January 10, 1901. Along the way, driller Curt Hamill needed to flush out the cuttings. He drove cattle into a nearby pond, and their milling-about produced the mud that, when pumped into the well, would bring up the cuttings. My dad didn't know his job, by then much more sophisticated, had developed almost in the backyard of our family home.

On my trip, I drove north through the pine forests, searched out the first steel oil tanks and toured the East Texas Oil Museum at Kilgore, not far from where I had started school. My mother, with me along as a child, had stopped at roadside stands for produce. Now I sought out fresh tomatoes, beans, and squash at farmers' markets in Lufkin and Tyler. Later a friend and I picked blueberries in an open field. An employee at a small restaurant in Jefferson was kind enough to wash and serve them with ice cream. And it is to Jefferson that I bring fellow travelers who long to taste the nostalgia for a simpler life during the Victorian period.

Texas is all things to all people. The mix of cultures has created a breed of people not unlike the longhorns, the tough cattle of crossed ancestry that also developed on this land. We Texans share the resourcefulness of the Dutch, the industry of Germans, the colorful dress of the Spanish, and the indomitable spirit of the British. To survive, many have to have the same toughness of the cattle. Survive, and thrive, they do.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)